Building the world of Lake: Terrain

Development

Authoring

Procedural terrain generation systems, such as World Machine, are ideal to simulate natural processes like hydraulic erosion (rain carving out channels) or sediment (flow and deposition of loose gravel and sand). These are vital for achieving natural and believable large scale terrains. Yet for games, it’s almost always required to accommodate gameplay or level design. For example: carving out a road, or flatten a specific area for building. Pure procedural generation tends to be ill-suited for this.

Ubisoft had achieved a harmony between procedural generation and manual authoring. I wholeheartedly aspired to do the same, in line with my embedded principle of using technology to facilitate creative flow.

The development of the landscape would be done alongside of the gameplay, narrative structure and infrastructure. Where I anticipated the need for locations may arise or become obsolete, or at least needing granular tweaking.

I wanted the freedom to alter the flow of the player’s movement through the world as we saw fit. Moving a hill a little further back to improvement the composition when driving down a particular road for instance. This meant the workflow would need to lend itself to easy and fast iteration, and most of all be non-destructive.

After seeing Ubisoft’s GDC presentation my perspective on world building was completely shifted. Ubisoft had achieved a harmony between procedural generation and manual authoring. I wholeheartedly aspired to do the same, in line with my embedded principle of using technology to facilitate creative flow and artistic freedom. In essence, the main drive behind me evolving into a Technical Artist.

After a bit of research I stumbled on World Creator, which featured the ability to sculpt the base terrain elevation through nodes laid out in a grid. And applying filters on top of it. Such as noise, erosion and specialized terrain features (eg. terracing or dunes).

What really made it stand out was the “Area” feature, allowing filters to be applied only to specific regions through an imported or painted mask. Combined, this all seemingly offered ample control over the terrain.

And yes, I was smitten! After having used nearly every tool for terrain authoring, this revolutionized the workflow!

Workflow

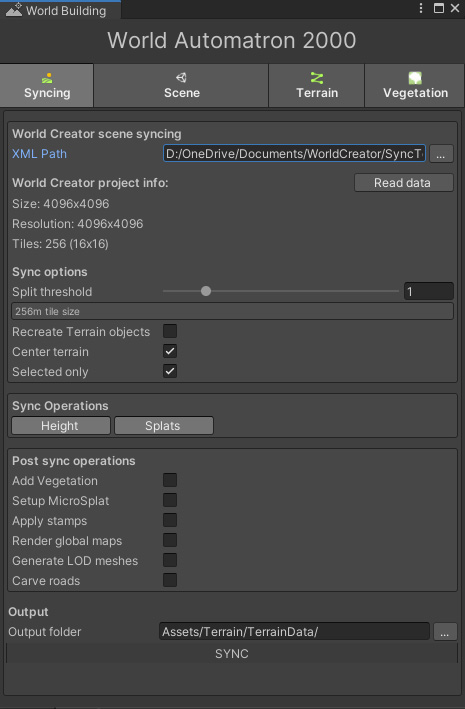

The accompanying “bridge” tool, which handles importing and converting World Creator’s data into Unity terrain, was functional, yet seemingly not fleshed out. It had the tendency of destroying all the terrains and recreating them. Resulting in all the terrain settings, added components and references being lost. None of the import settings were being saved and there was no control over where the data was stored.

There was never any objection from those overseeing the scope and planning of the project when I proposed to spent a few days on workflow polishing. That’s definitely a level of professional freedom I don’t take for granted!

All in all this hindered the workflow, and required terrain changes to be carefully planned for. Seeing as it involved spending time on restoring other aspects of the environment (eg. terrain shader, vegetation, centering the terrain). Afterwards, it was very frustrating to find out something small was missed, but had to be pushed back to the next iteration.

In order to achieve a smooth and carefree workflow, the bridge tool was modified over time. Settings were stored in a ScriptableObject, destroying terrains was optional and syncing only Height or Splatmap data, or just the terrains in view was now possible.

Additionally, C# callbacks were exposed so post-processing scripts could be launched after the terrain was synced. Eventually this involved respawning vegetation, carving roads, reapplying stamps and regenerating LODs.

This all was worth the effort, as it was now possible to quickly iterate on the terrain and automate any subsequent processes. There was never any objection from those overseeing the scope and planning of the project when I proposed to spent a few days on workflow polishing. That’s definitely a level of professional freedom I don’t take for granted!

World Creator to Unity workflow in action:

As the landscape started to converge on finer (human-scale) details it became increasingly difficult to make small-scale adjustments. When working in World Creator, it’s simply not possible to see what’s supposed to be there inside Unity. This makes for a lot of guesswork through tiny adjustments, syncing, then observing the result. Making these changes by hand wouldn’t be viable, since these would be lost after syncing from World Creator. Otherwise requiring to close the door on any large-scale terrain modifications forever.

The Mercator asset came up after looking for a solution, which enables a terrain to be modified through selective stamps. This would enable a specific area to be flattened to raised for something like a building. Unfortunately, in practice the tool wasn’t making things easier. It was designed around the use case of creating the terrain entirely using its stamps, and didn’t support a tiled terrain set up. Unfortunately, it also brought the editor’s performance to a crawl.

The functional concept behind it is rather simple. Given that a terrain’s heightmap is a texture map, it’s certainly possible to modify it through a shader. Which is essentially how the built-in terrain sculpting tool works. It “injects” a rectangle, with a brush texture, into the terrain heightmap, and applies the result by blending both.

One faithful morning, I decided to simply have a stab at a prototype for this. Surprisingly, after a mere few hours I already had a proof of concept, where any texture/brush could be blended into the heightmap. Since the brush is applied to a flat quad mesh under the hood, adding support for other meshes was very straightforward, making splines a possibility.

Excited about the potential added control, I spent more time on it to develop it into a standalone tool, before eventually trying it out in the Lake project.

Unfortunately, stamps have to be made permanent at some point, before they can relinquish control of a terrain, which actually goes against the non-destructive design philosophy I’d established. Unity’s terrain system could greatly benefit from a layer system.

But since the “original” terrain can at any point be restored by syncing from World Creator, this never got in the way. Eventually, stamps would simply automatically get applied after syncing. In the end, a little under 400 stamps were used to flatten out areas, add details or to remove any unwanted bumps.

An artist asked me how they could paint dirt underneath a house, to which I had to reply “You basically can’t”. It suck with me how silly this sounded. Which prompted the idea to extend the tool with the needed functionality to use stamps for painting terrain materials. As well as support for using splines as stamps, to create dirt paths.

In hindsight, without the stamping functionality, the finer stages of the terrain development would likely have become extremely painstaking. It allowed the non-destructive workflow to be maintained, and made large scale terrain adjustments still possible. Bear Creek for instance, was moved across the map at one point!

The only thorn in my side was that the road network created using Easy Roads 3D, it modifies the terrain using scripting, rather than also being GPU-based. This meant the roads had to be carved using its functionality, after syncing, but before working with stamps. Annoyingly, this modified all the terrain data, making for a version control nuisance.

Tools & Utilities

For a long time, the map used in the game (doubles as the minimap) was a top-down render of the terrain as it appears with completely flat lighting, resulting in an albedo texture. A few experiments required to also have access to the global terrain height- and normal map, namely for the low-detail distance terrains.

To create these texture maps easily, and repeat-able after terrain modifications were made, a tool was created to achieve just that. With just the heightmap, a normal map could be derived. Which in turn made generating other type of textures possible.

Having access to these textures made it rather straightforward to use Photoshop and reconstruct 3D-esque lighting. This involved a lovely tangent into the world of DEMs and a bit of cartography. Which helped to understand how real-world maps were created from similar data.

Optimization

Using a single 8x8km terrain quickly proved to not be viable. Even with a massive 4k heightmap it meant a vertex was placed at every 2 meters. To provide enough accuracy for a smooth terrain at least 1 vertex every 0.5 units/meter would be needed.

This translated to a 16k heightmap. In addition to a 8-16k splatmap for every 4 textures used on the terrain. Pressing play make the editor freeze for about 30 seconds, due to the huge chunk of data that had to be loaded into memory. It became clear the terrain needed to be segmented into tiles, and loaded in/out around the player as it moved around the world.

My attention quickly fell on the World Streamer asset, which promised to do just that. After reading through the extensive documentation on my commute, it was implemented for the terrain. There is much to say about this asset, unfortunately not in the most positive sense. Throughout development we encountered so many issues and quirks, making our own streaming system was considered. Yet, broadly speaking, it provided a service early on that was vital and eventually worked.

With the terrain split up into tiles, 9 of them would be loaded around the player at all times. This dramatically improved the initial loading times. Though finding the right balance between terrain size and height- & splatmap resolution was a long-term process!

The gaps seen here aren’t visible in the game, this is recorded with both the scene- and game view open, greatly affecting loading performance

Though this meant there was no longer any terrain or vegetation to be seen in the distance. In order to make up for this, for every terrain tile a “mesh terrain” is activated when a terrain is disabled . This being a low-detail version of a real terrain tile.

Originally, each tile was a unique mesh, shaped to the terrain it was supposed to represent. Generated as syncing post-process action. But with each tile being unique, the game had a near constant 200 draw calls being “wasted” on them.

Once the terrain map rendering tool was in place, a flat (but normal mapped) subdivided plane mesh was used instead. Where the vertices would be displaced upwards in a vertex shader by the global terrain heightmap texture, giving it its shape. As a result, the mesh terrains rendered in a single draw call thanks to GPU Instancing!

This technique is unfortunately not impervious to cracks. Where the vertices of a terrain and mesh-terrain aren’t matching up. Yet, since the terrain was mostly covered with vegetation and rocks, these were rarely visible.

Towards the end of the project, terrain tiles that weren’t practically visible were removed from the world. This ended up being about 20% of all 256 tiles.

Could have’s

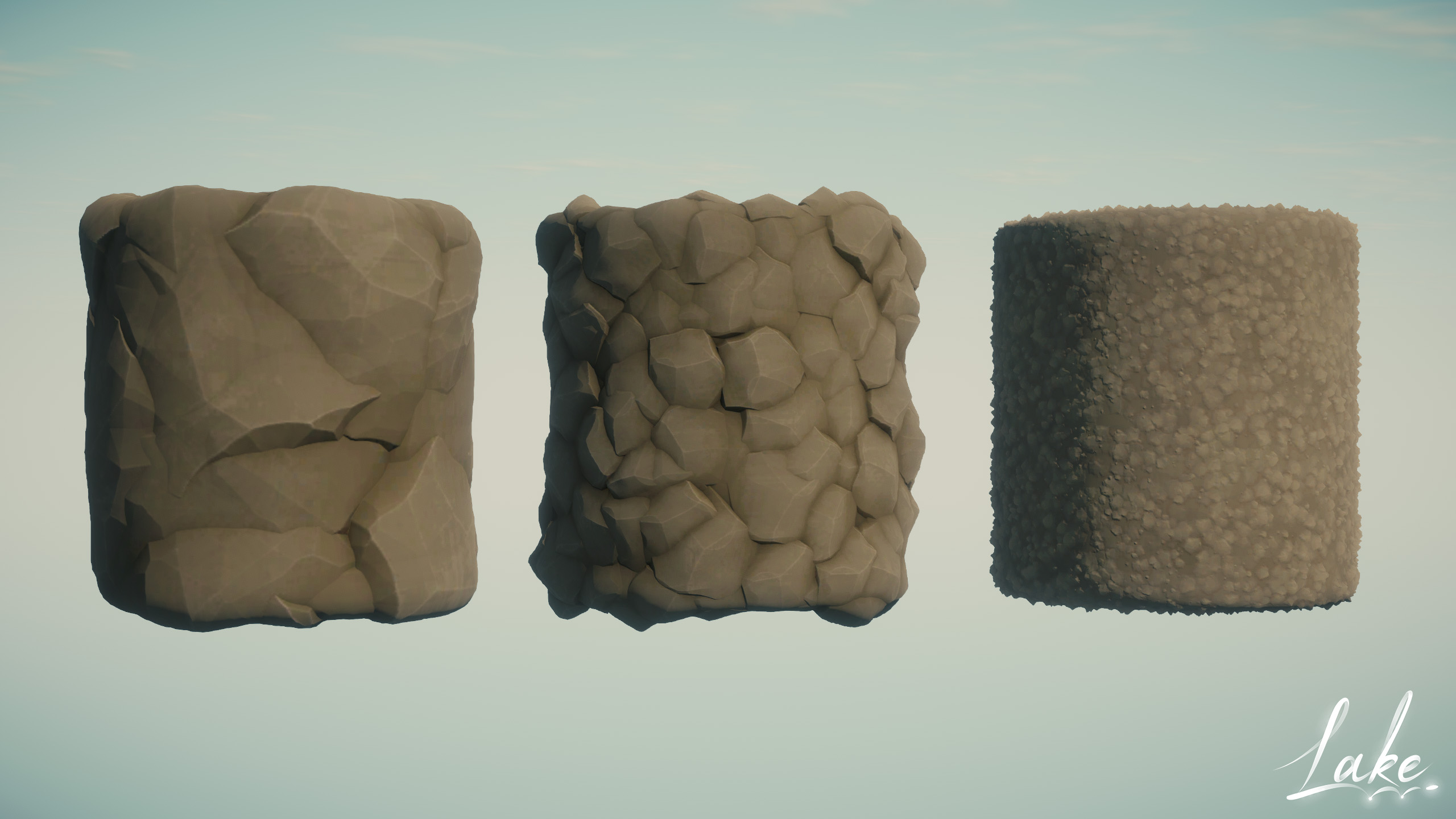

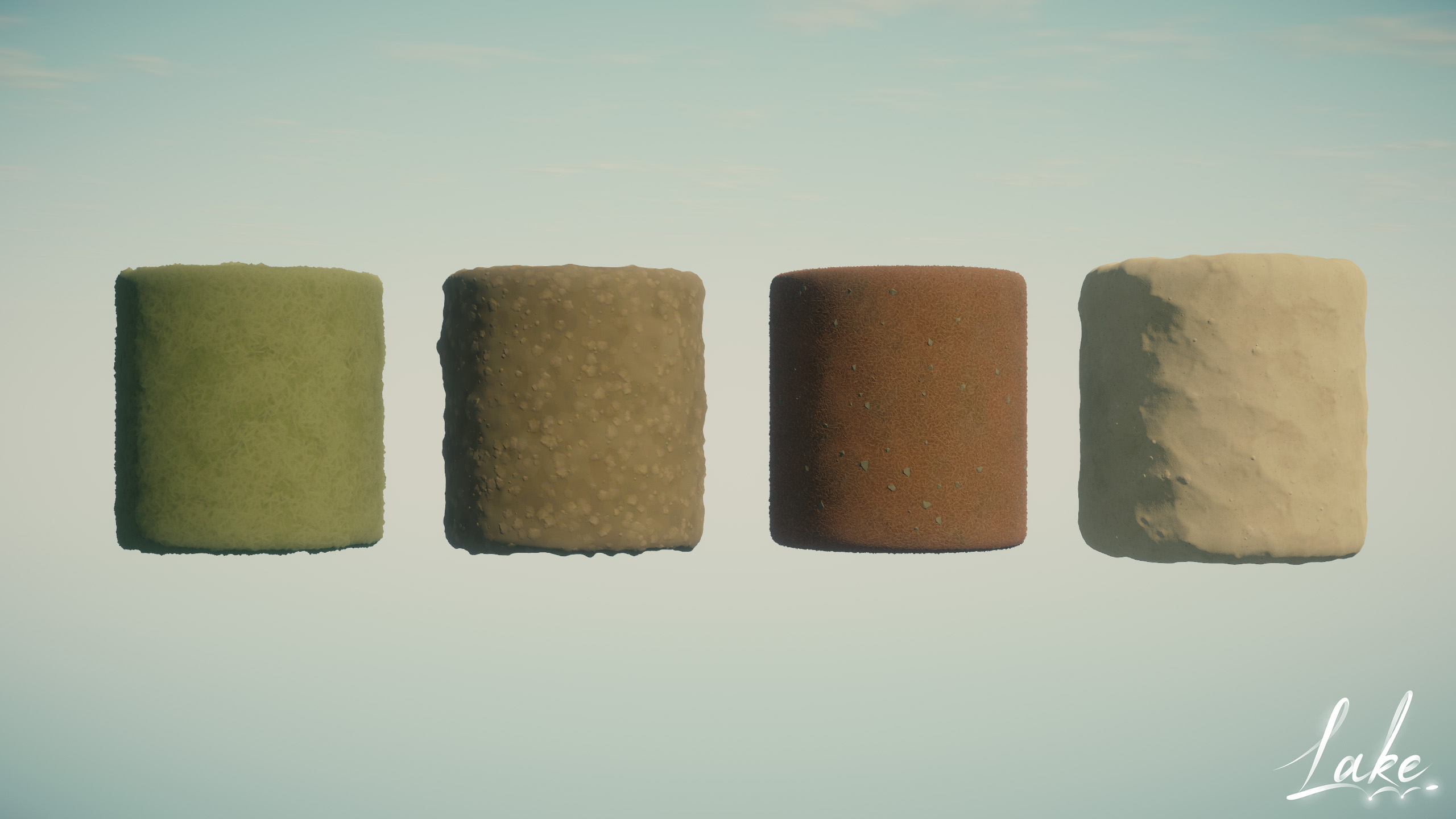

Terrain resolution and materials

The terrain resolution and number of textures was always limited. When a terrain data asset was larger than 800kb, a hiccup became noticeable when a terrain loaded in, particularly on devices without an SSD.

I later learned that Vegetation Studio has a certain amount of overhead when a terrain is added/removed. Eventually, vegetation was spawned on a flat plane underneath the world instead (the positions are pre-baked anyway). As a result, vegetation was only initialized once, at the start of the game.

During a hefty optimization round for the Xbox build, we learned that simply loading a scene has a large amount of overhead in Unity. Even if the scene is empty. Some third-party assets were also performing expensive operations when this happened. We opted to simply load all the stream-able scenes at the start, and simply toggle the contents on/off. So much easier on the CPU.

Both these aspect led me to believe the terrain itself was too heavy, and had to be limited. After these optimizations there was room for more terrain detail, but everything was already built on solid foundations.

Cross blending between terrain layers

Some terrain materials weren’t blending properly. For example, dirt covering grass where they meet. Rather than grass protruding through thin layers of dirt. This has everything to with the order these layers are assigned to terrains. Which is controlled in World Creator. I was unable to change this when I learned about this, as it involved restructuring the way texturing was done in World Creator.